Western bean cutworm, Striacosta albicosta, is native to North America, where it has traditionally been found in the United States (western Great Plains, including Idaho, Montana, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas). Since 2000, the range of western bean cutworm has expanded to the east in both the United States and Canada, and is now found in Ontario, Quebec, and Nova Scotia (as of 2017).

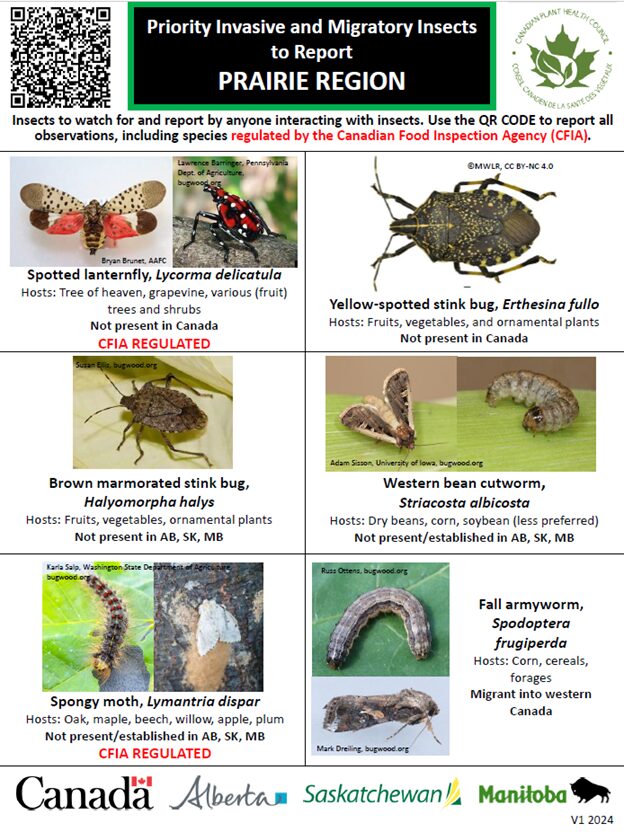

Western bean cutworm is not present or established in Alberta, Saskatchewan, or Manitoba.

It is important for farmers in western Canada to be on the lookout for western bean cutworm because this insect is a serious pest of corn and of dry edible beans (Phaseolus spp.). Larvae of western bean cutworm feed on developing corn ears and bean pods, resulting in direct injury to the harvested parts of these crop plants. In beans, the first and second instar larvae also feed on the leaves and flowers. In corn, damage can be observed on the silk, as well as the cobs and kernels. Damage caused by western bean cutworm increases the susceptibility of the plants to fungal infection, which can further decrease seed quality and yields.

In the adult stage, male and female western bean cutworm can be distinguished from other cutworm moths by a pale tan band on the leading edge of the forewing and by a spot and comma-shaped mark in the same pale tan colour located near the middle of the forewings. Adult moths are most active in mid- to late July and fly mostly at night. Eggs are laid in masses, with about 50-80 eggs on average. The eggs are white when first laid and darken to a light tan colour and then to a purple colour just before hatching. Larvae, especially from the 4th instar on, are characterized by the presence of 2 black stripes behind the head. The larvae are smooth and fairly hairless.

For more information and pictures, please refer to the Canadian Corn Pest Coalition factsheet and the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness factsheet on western bean cutworm.

Please report insects or damage resembling western bean cutworm to Dr. Meghan Vankosky (meghan.vankosky@agr.gc.ca).

Information for this Insect of the Week post was summarized from an Open Access paper: Smith, J.L., C.D. Difonozo, T.S. Baute, A.P. Michel, and C.H. Krupke. 2019. Ecology and management of the western bean cutworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in corn and dry beans – Revision with focus on the Great Lakes Region. Journal of Integrated Pest Management 10: 27 https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmz025