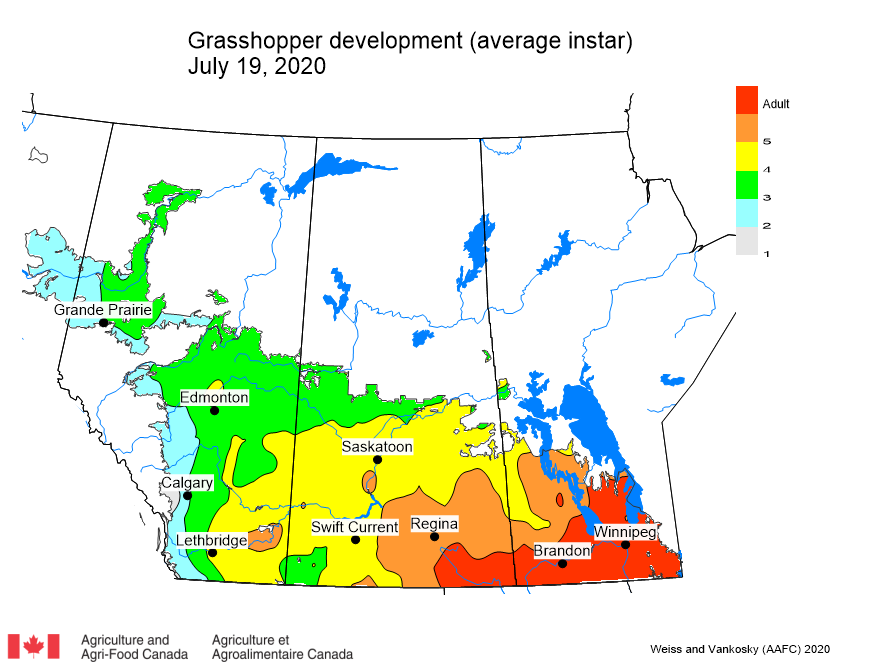

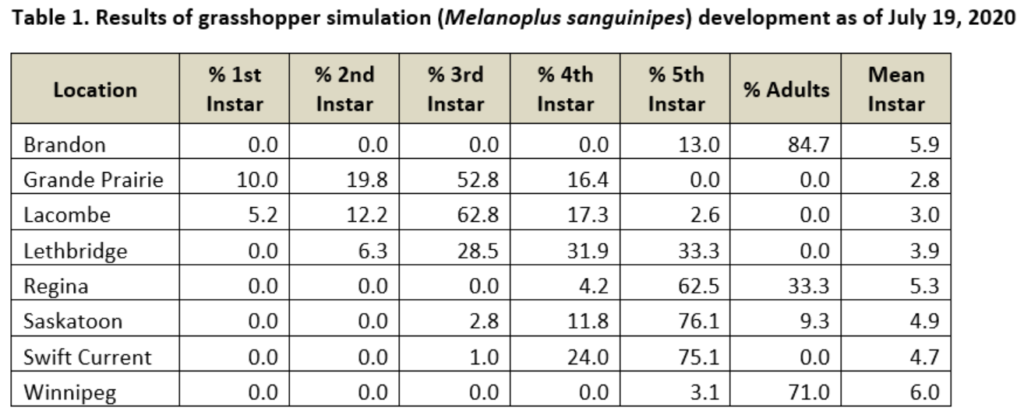

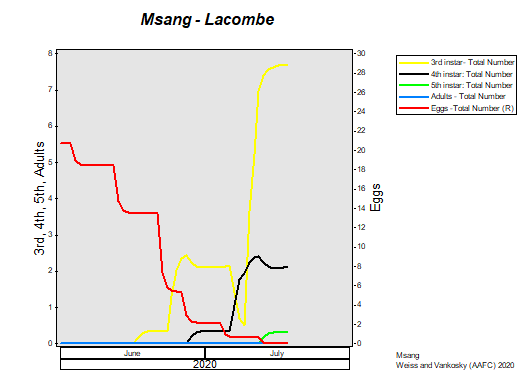

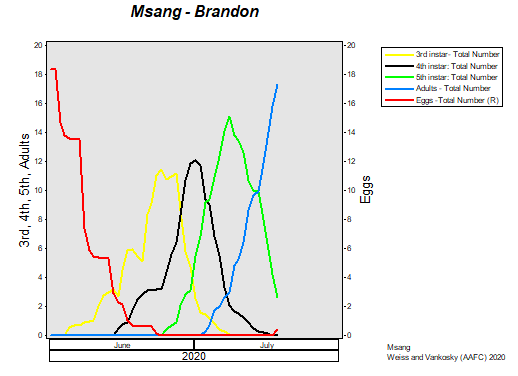

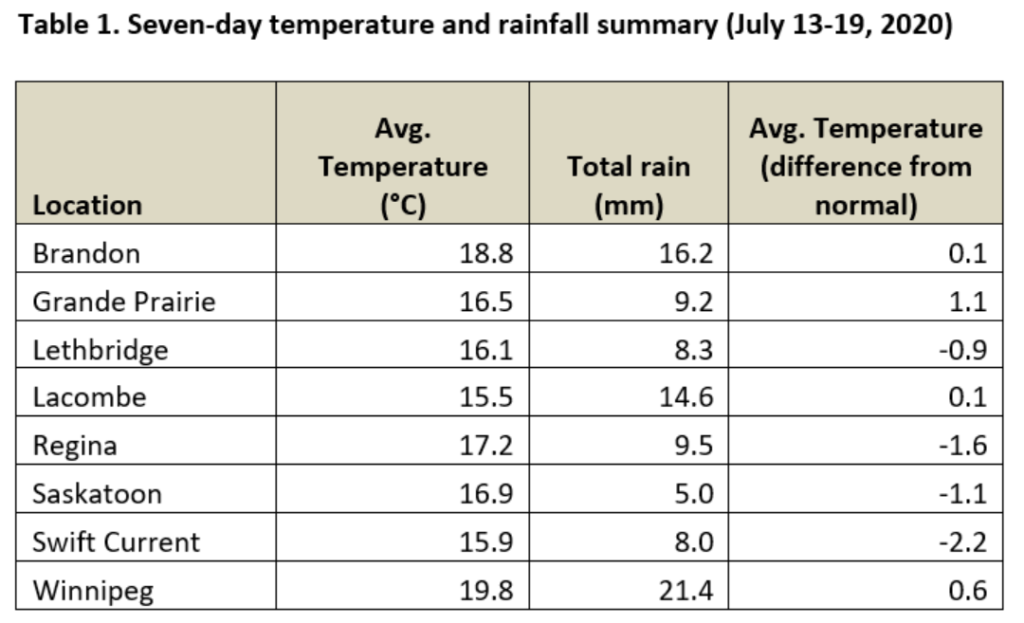

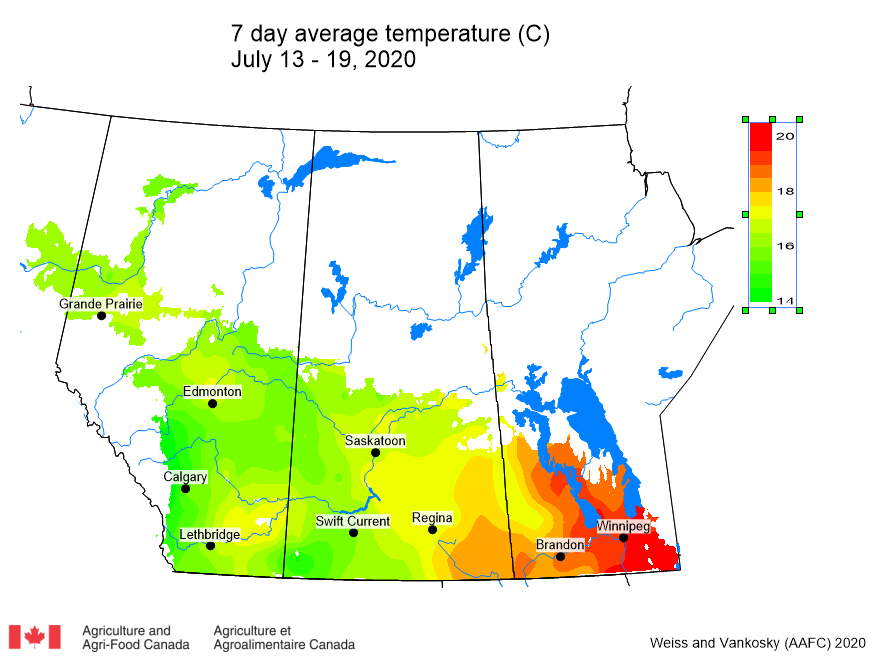

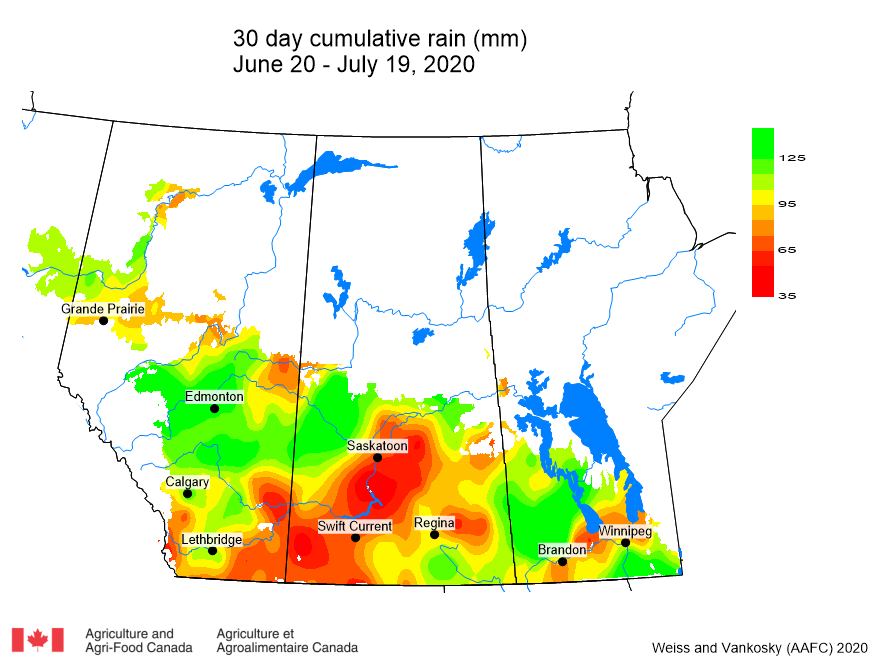

This past week (July 13-19, 2020) prairie temperatures were warmest in Manitoba and eastern Saskatchewan (Table 1; Fig. 1). Average 7-day temperatures continue to be warmest across Manitoba and eastern Saskatchewan and coolest across most of Alberta(Table 1; Fig. 1).

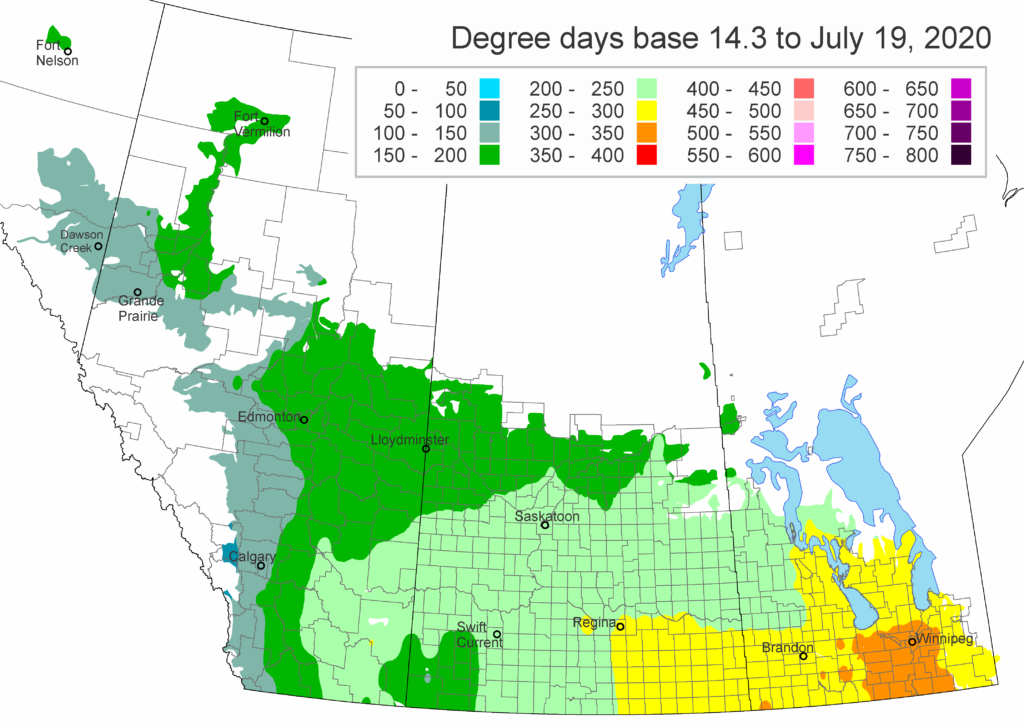

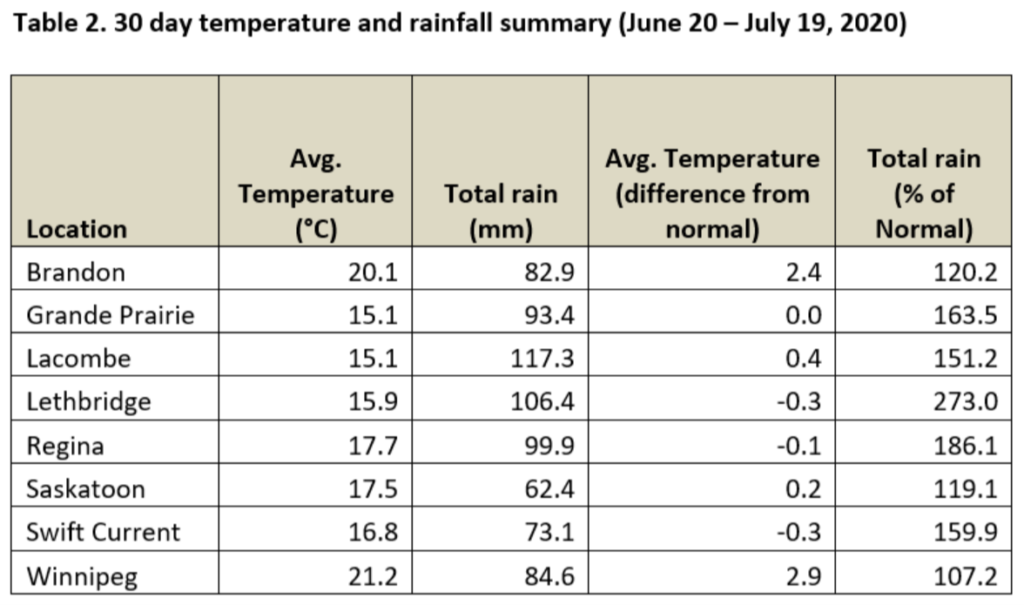

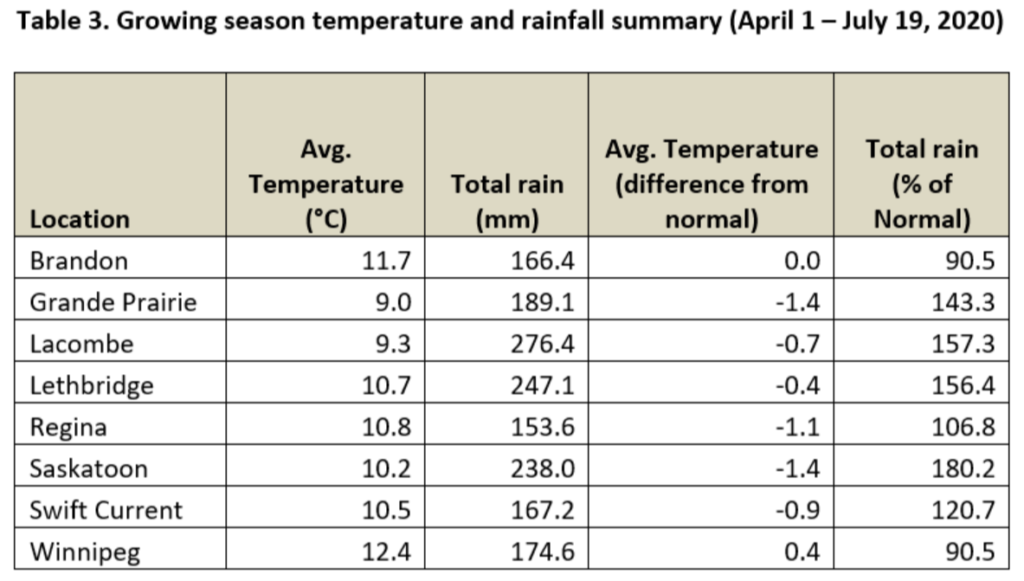

Average 30-day (June 20-July 19, 2020) temperatures continued to be cooler in Alberta than eastern Saskatchewan and Manitoba (Table 2; Fig. 2). The average 30-day temperature at Winnipeg and Brandon continued to be greater than locations in Alberta and Saskatchewan(Table 2; Fig. 2). Based on growing season temperatures (April 1 – July 19, 2020), conditions continue to be warmest for southern locations (Table 3).

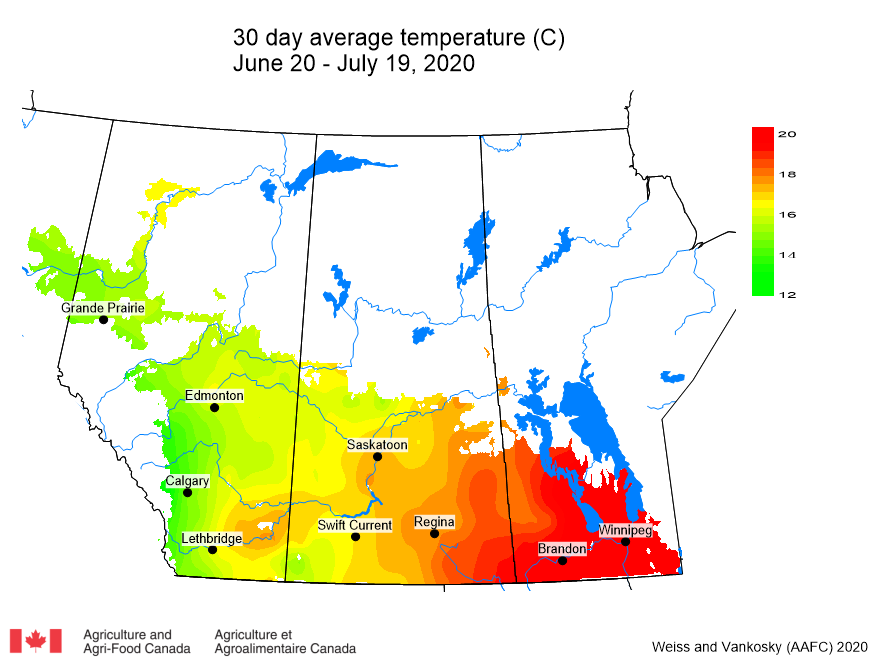

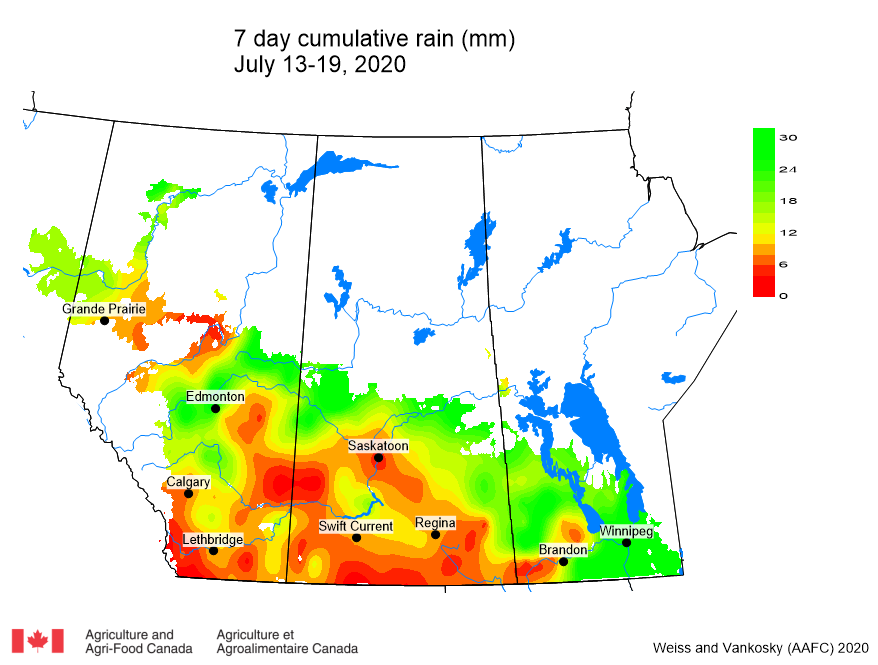

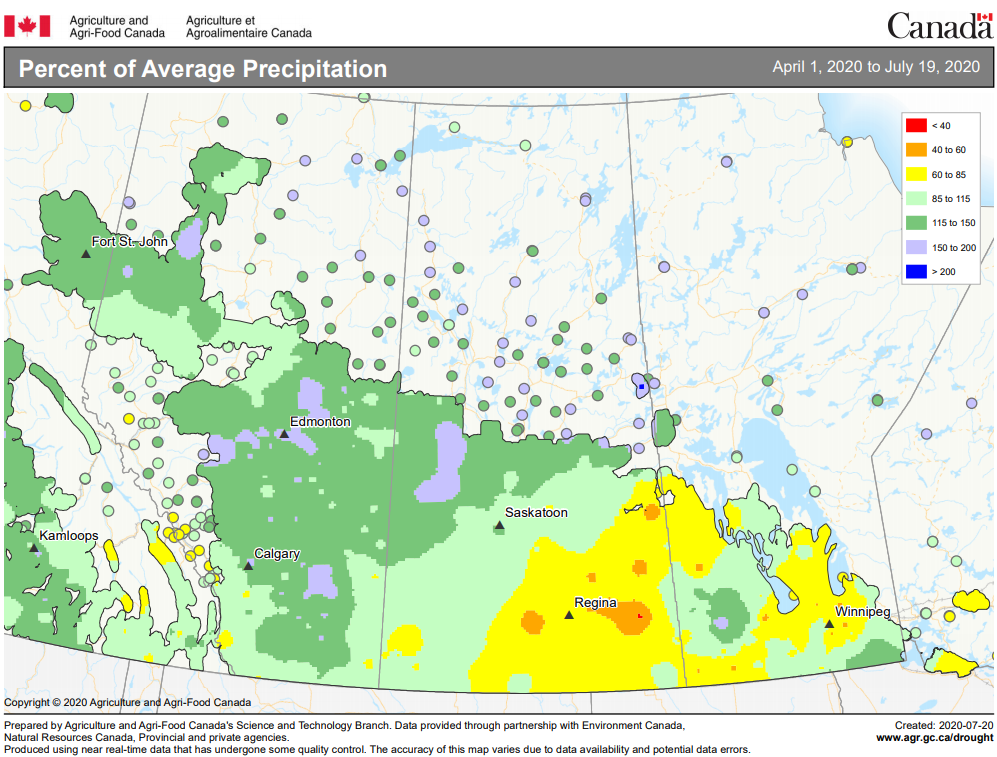

Cumulative rainfall for the past 7 days was lowest across southern regions of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Cumulative 30-day rainfall was lowest across a large area ranging from southwest Saskatchewan to Saskatoon. Growing season rainfall (percent of average) is below normal across eastern Saskatchewan and localized areas of Manitoba.

Image has not been reproduced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada and was retrieved (21Jul2020). Access the full map at http://www.agr.gc.ca/DW-GS/current-actuelles.jspx?lang=eng&jsEnabled=true&reset=1588297059209

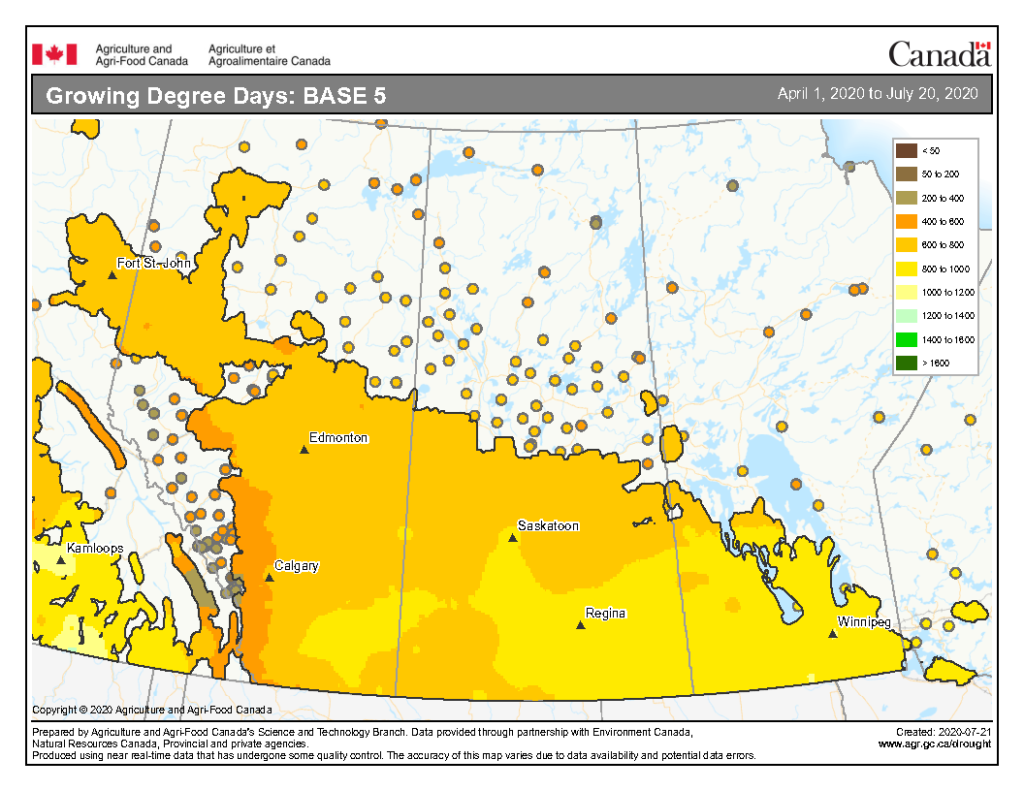

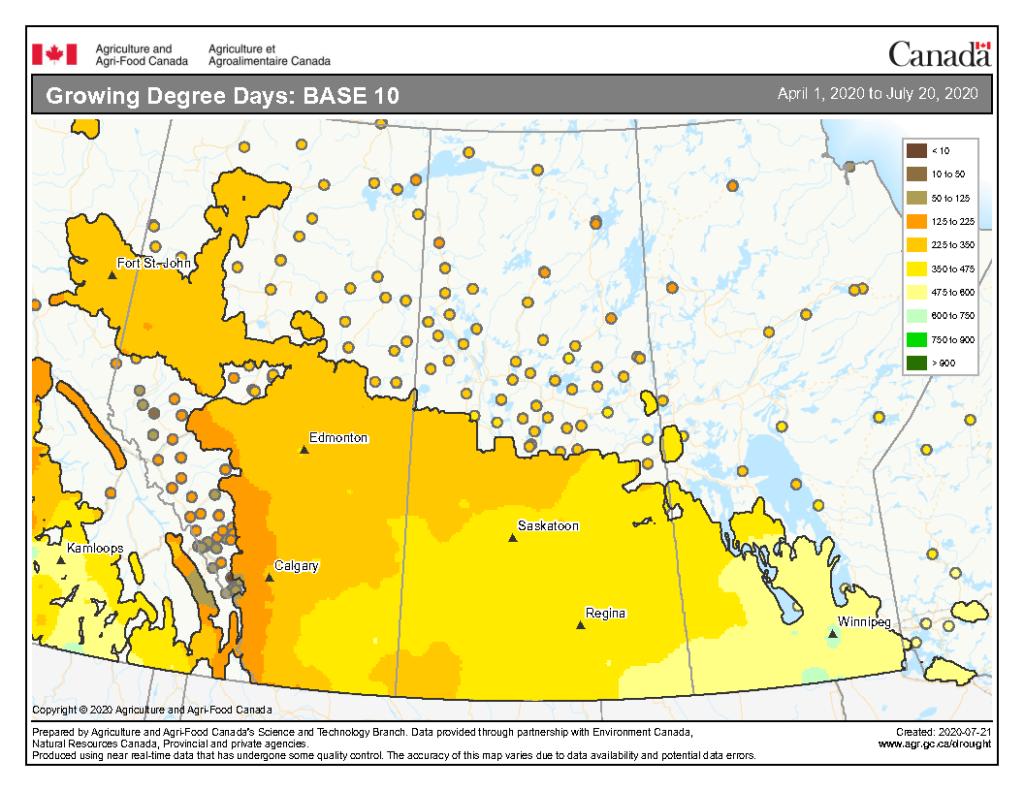

The growing degree day map (GDD) (Base 5 ºC, April 1-July 13, 2020) is below (Fig. 7) while the growing degree day map (GDD) (Base 10 ºC, April 1-July 13, 2020) is shown in Figure 8.

Image has not been reproduced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada and was retrieved (23Jul2020). Access the full map at http://www.agr.gc.ca/DW-GS/current-actuelles.jspx?lang=eng&jsEnabled=true&reset=1588297059209

Image has not been reproduced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada and was retrieved (23Jul2020). Access the full map at http://www.agr.gc.ca/DW-GS/current-actuelles.jspx?lang=eng&jsEnabled=true&reset=1588297059209

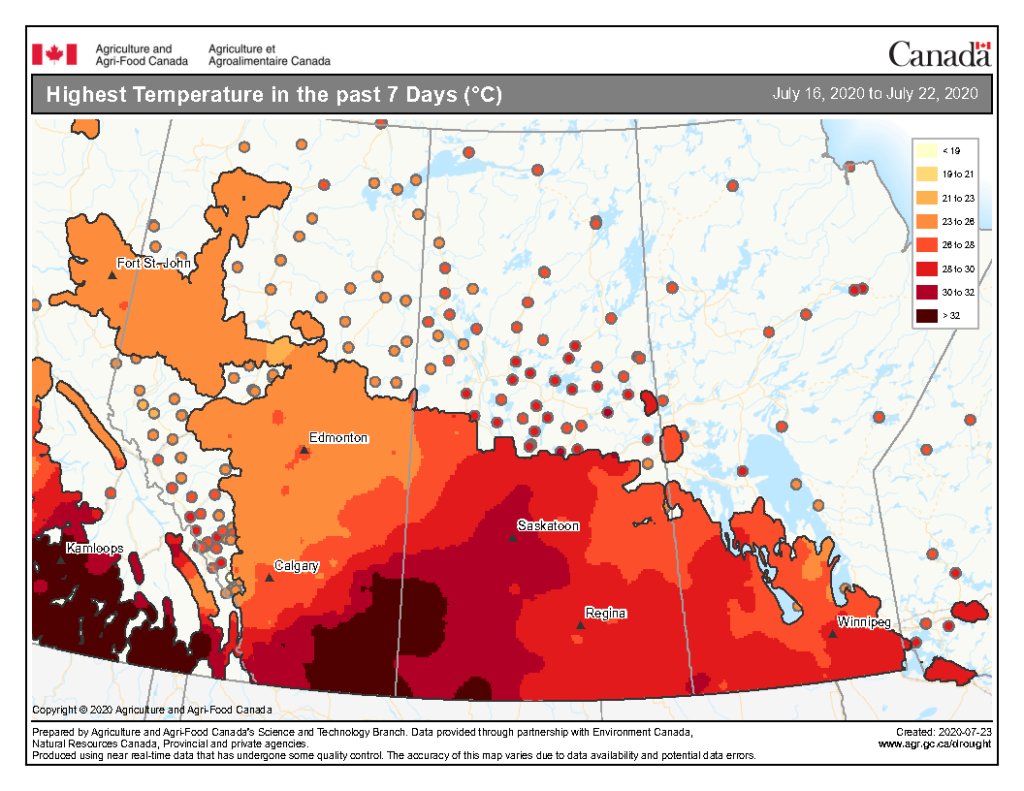

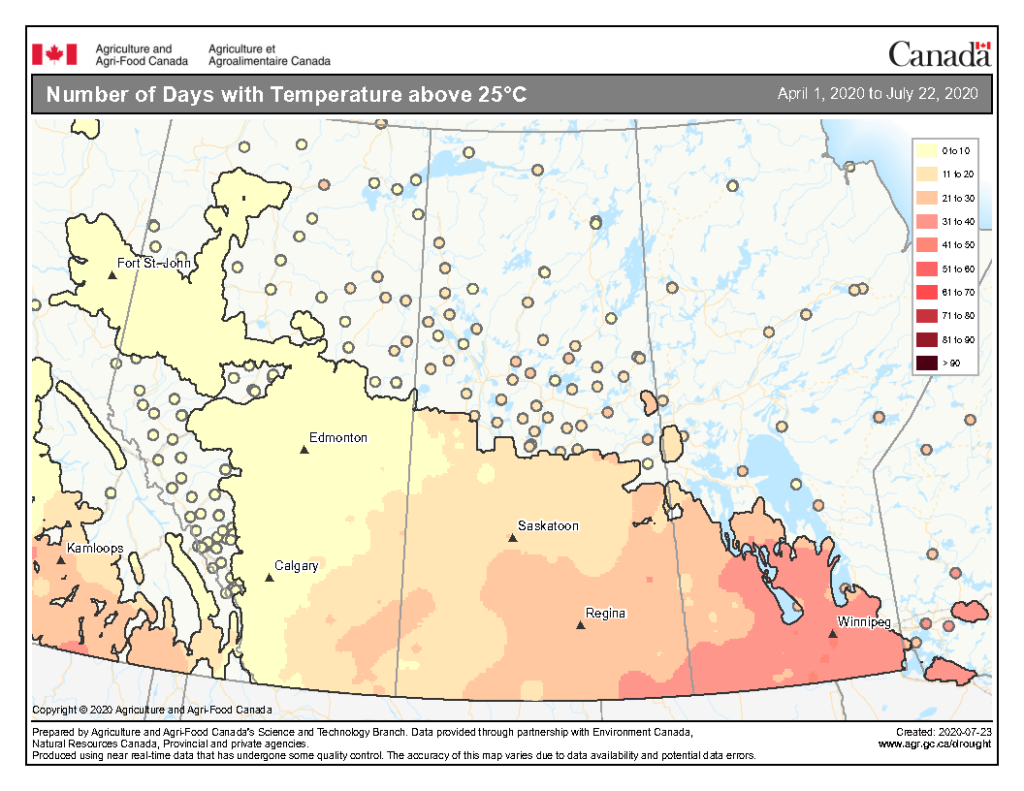

The highest temperatures (°C) observed across the Canadian prairies the past seven days ranged from <19 to >32 °C (Fig. 9). So far this growing season (up to July 22, 2020), the number of days above 25 ranges from 0-10 days throughout much of Alberta and into the BC Peace then extends up to 41-50 days in southern Manitoba (Fig. 10).

Image has not been reproduced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada and was retrieved (23Jul2020). Access the full map at http://www.agr.gc.ca/DW-GS/current-actuelles.jspx?lang=eng&jsEnabled=true&reset=1588297059209

Image has not been reproduced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada and was retrieved (23Jul2020). Access the full map at http://www.agr.gc.ca/DW-GS/current-actuelles.jspx?lang=eng&jsEnabled=true&reset=1588297059209

The maps above are all produced by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Growers can bookmark the AAFC Current Conditions Drought Watch Maps for the growing season. Historical weather data can be access at the AAFC Drought Watch website, Environment Canada’s Historical Data website, or your provincial weather network.