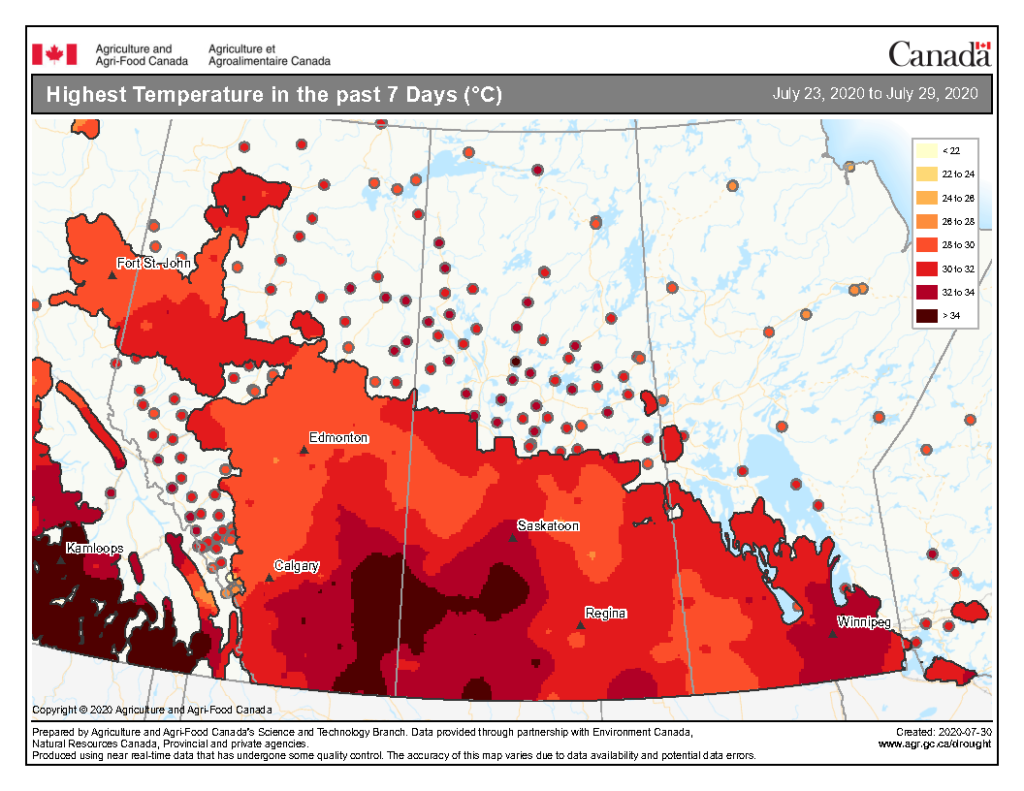

An abbreviated synopsis of the past week is provided below. Recent warm weather across the Canadian prairies helped crop development this past week

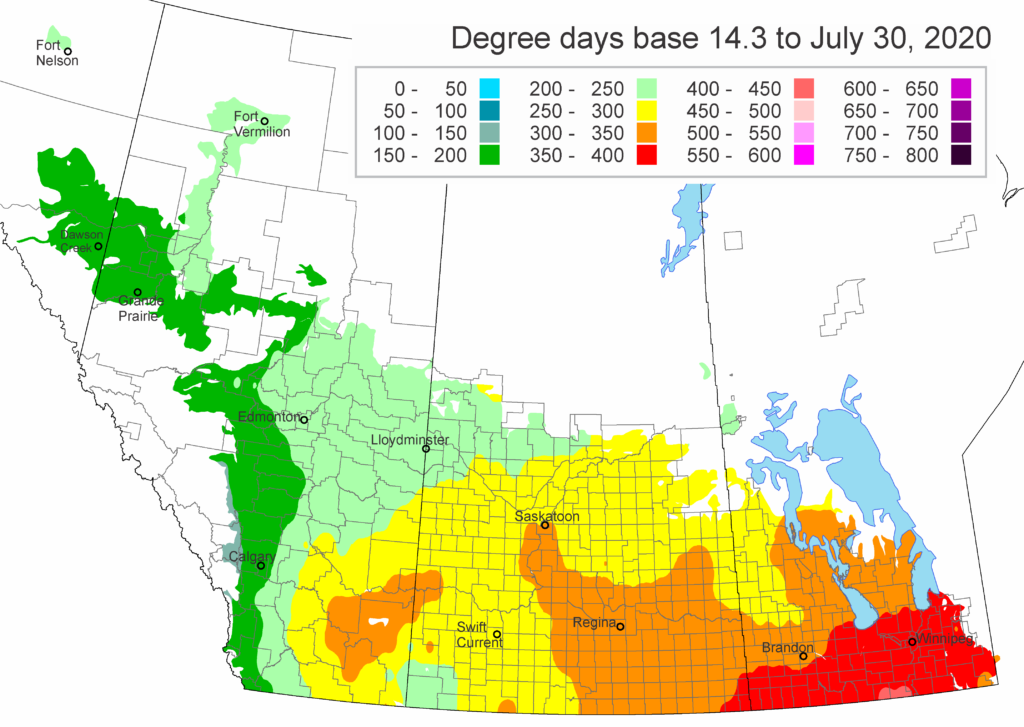

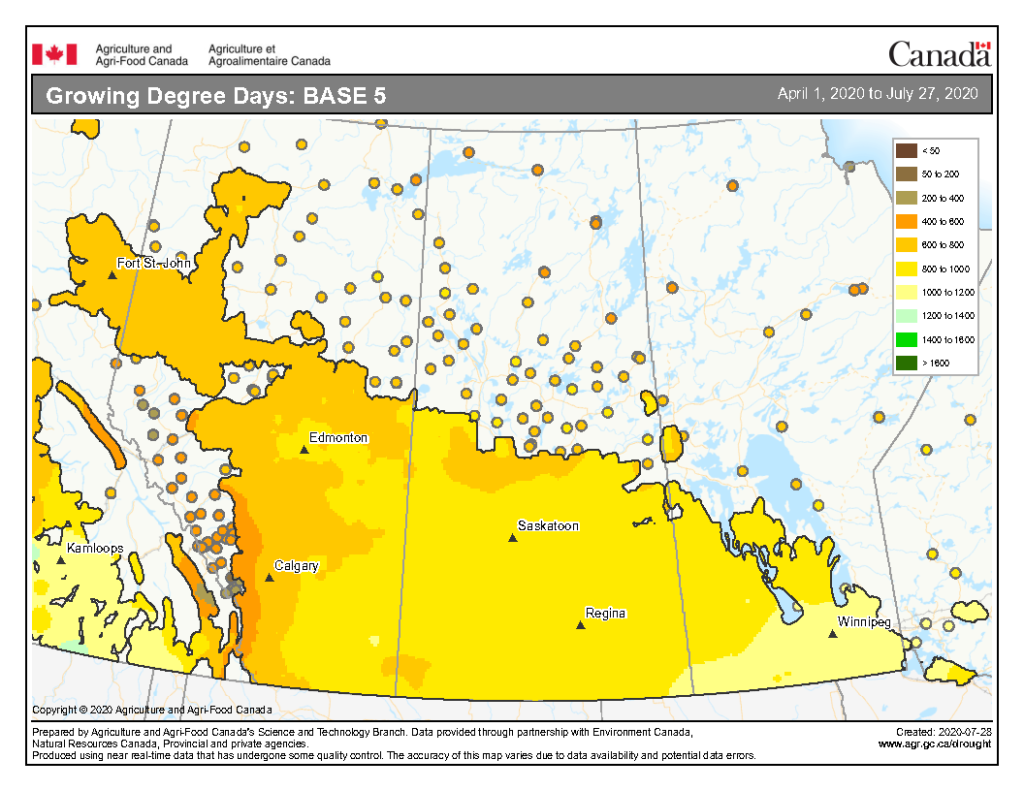

The growing degree day map (GDD) (Base 5 ºC, April 1-July 27, 2020) is below (Fig. 1) while the growing degree day map (GDD) (Base 10 ºC, April 1-July 27, 2020) is shown in Figure 2.

Image has not been reproduced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada and was retrieved (30Jul2020). Access the full map at http://www.agr.gc.ca/DW-GS/current-actuelles.jspx?lang=eng&jsEnabled=true&reset=1588297059209

Image has not been reproduced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada and was retrieved (30Jul2020). Access the full map at http://www.agr.gc.ca/DW-GS/current-actuelles.jspx?lang=eng&jsEnabled=true&reset=1588297059209

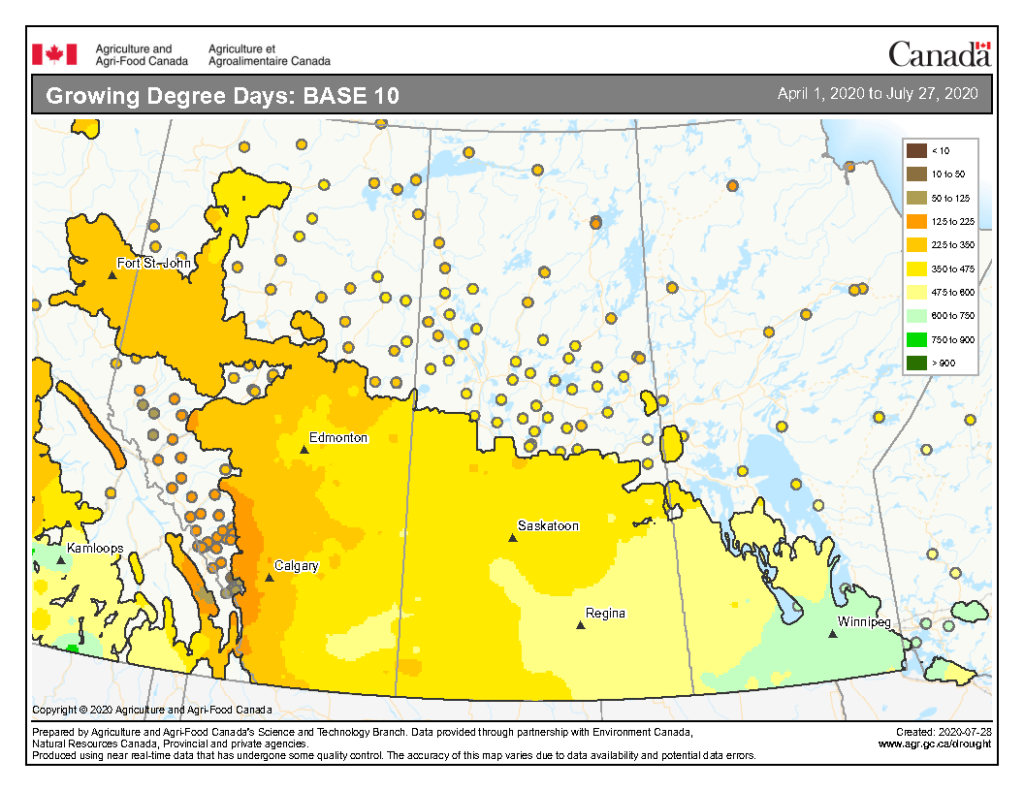

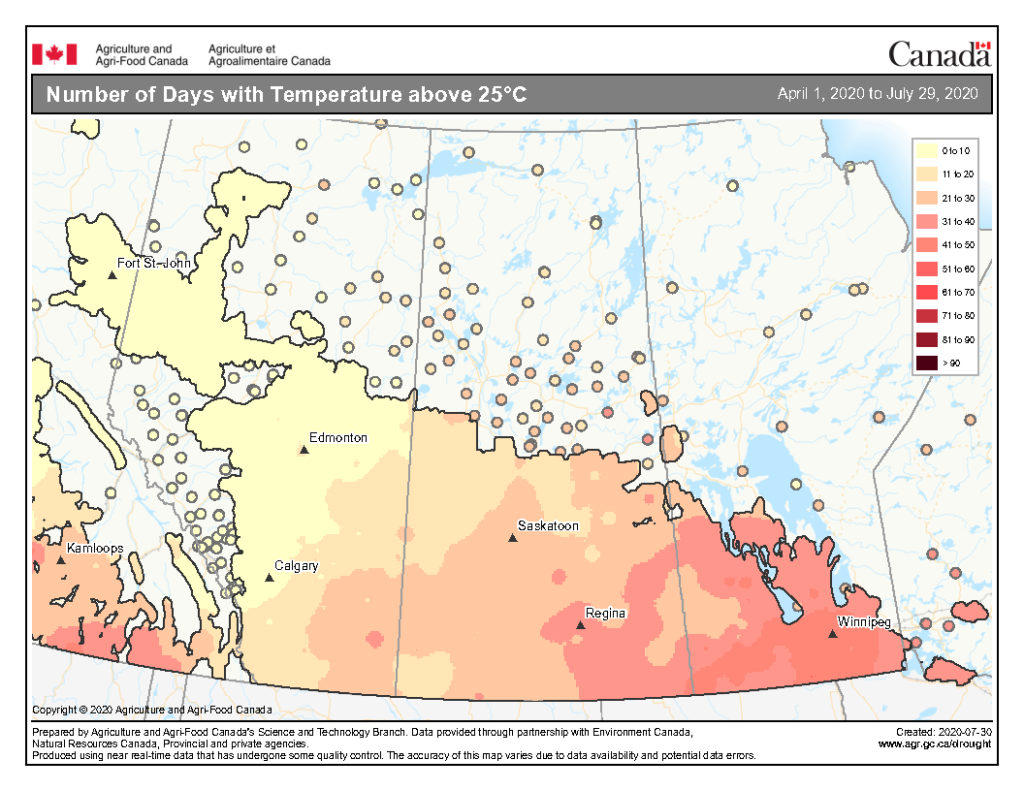

The highest temperatures (°C) observed across the Canadian prairies the past seven days ranged from <22 to >34 °C (Fig. 3). So far this growing season (up to July 29, 2020), the number of days above 25 ranges from 0-10 days throughout much of Alberta and into the BC Peace then extends up to 41-50 days in southern Manitoba (Fig. 4).

Image has not been reproduced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada and was retrieved (30Jul2020). Access the full map at http://www.agr.gc.ca/DW-GS/current-actuelles.jspx?lang=eng&jsEnabled=true&reset=1588297059209

Image has not been reproduced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada and was retrieved (30Jul2020). Access the full map at http://www.agr.gc.ca/DW-GS/current-actuelles.jspx?lang=eng&jsEnabled=true&reset=1588297059209

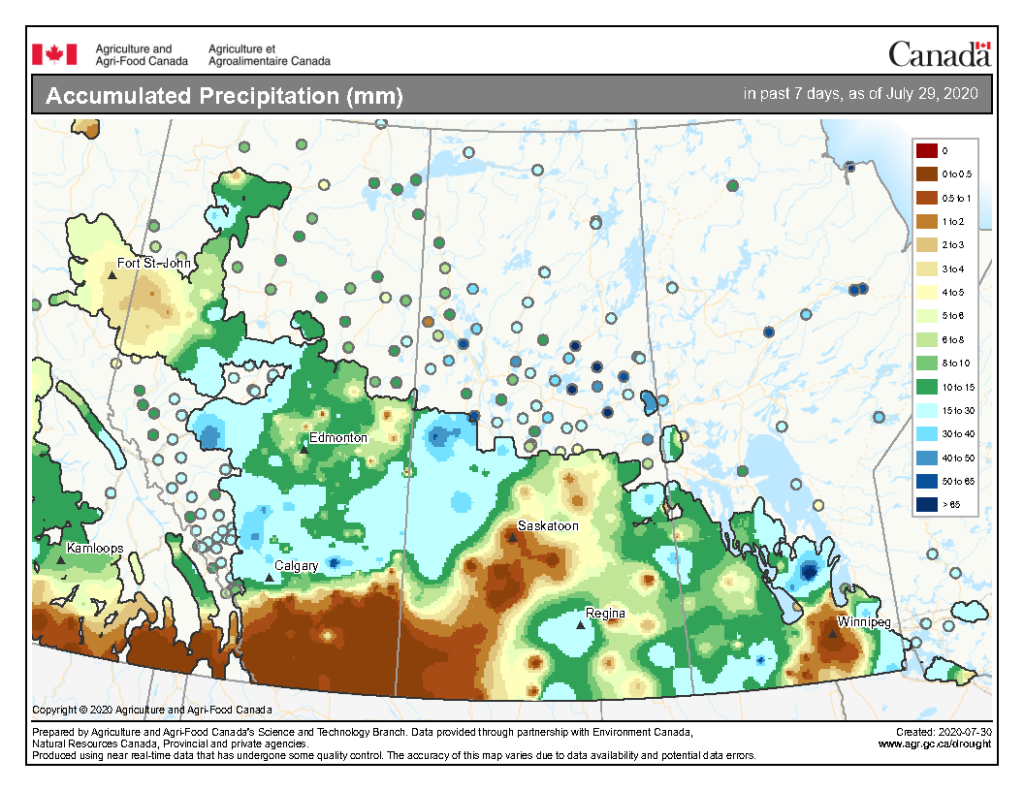

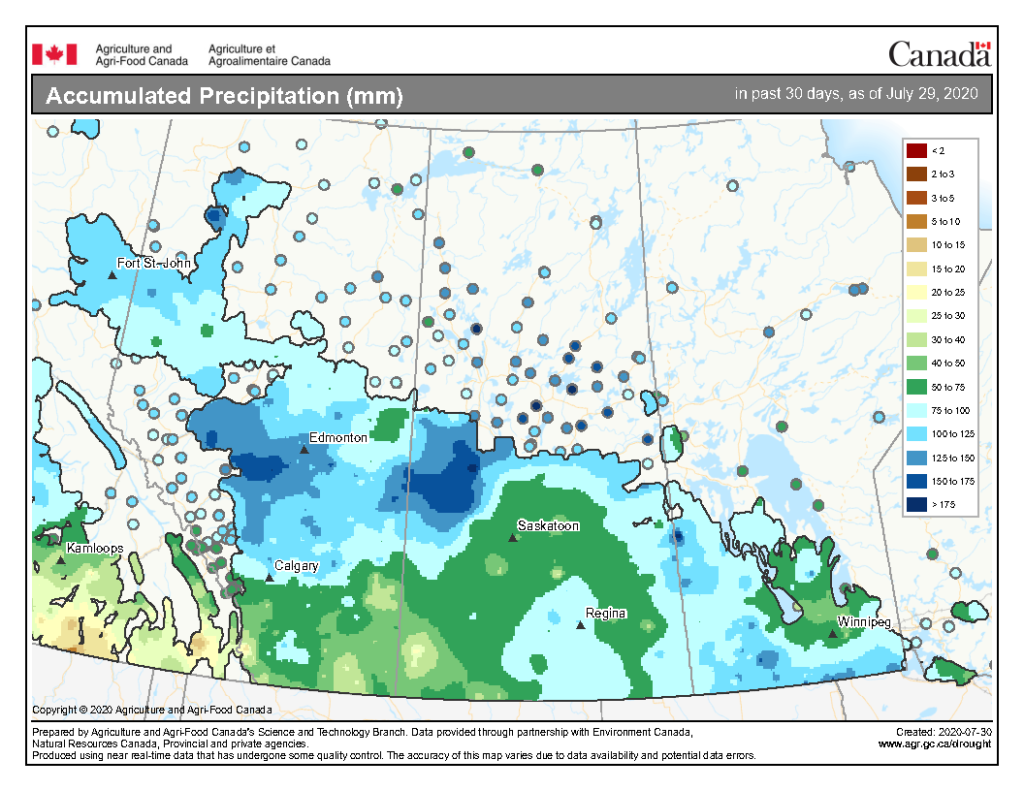

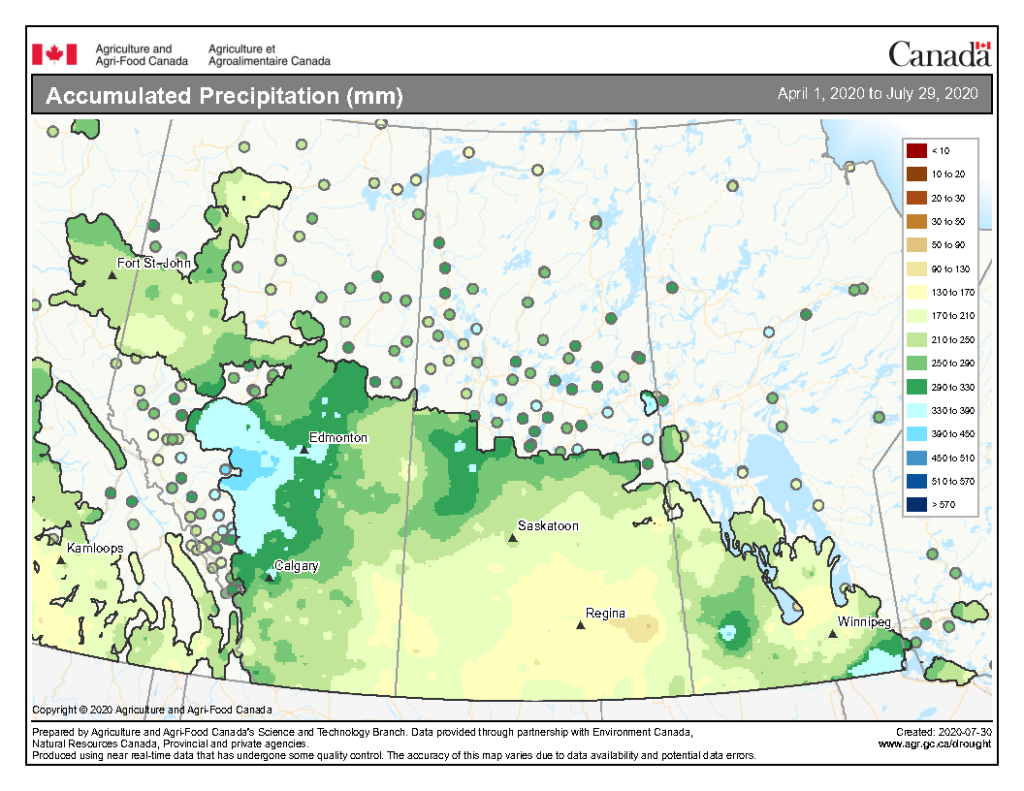

Cumulative rainfall for the past 7 days was lowest across southern regions of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba with the exception of around Regina south to the American border, and southwest Manitoba west into the southeast corner of Saskatchewan (Fig. 5). Cumulative 30-day (Fig. 6) and rainfall for the growing season (April 1-July 29, 2020; Fig. 7) are below.

Image has not been reproduced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada and was retrieved (30Jul2020). Access the full map at http://www.agr.gc.ca/DW-GS/current-actuelles.jspx?lang=eng&jsEnabled=true&reset=1588297059209

Image has not been reproduced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada and was retrieved (30Jul2020). Access the full map at http://www.agr.gc.ca/DW-GS/current-actuelles.jspx?lang=eng&jsEnabled=true&reset=1588297059209

Image has not been reproduced in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada and was retrieved (30Jul2020). Access the full map at http://www.agr.gc.ca/DW-GS/current-actuelles.jspx?lang=eng&jsEnabled=true&reset=1588297059209

The maps above are all produced by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Growers can bookmark the AAFC Current Conditions Drought Watch Maps for the growing season. Historical weather data can be access at the AAFC Drought Watch website, Environment Canada’s Historical Data website, or your provincial weather network.