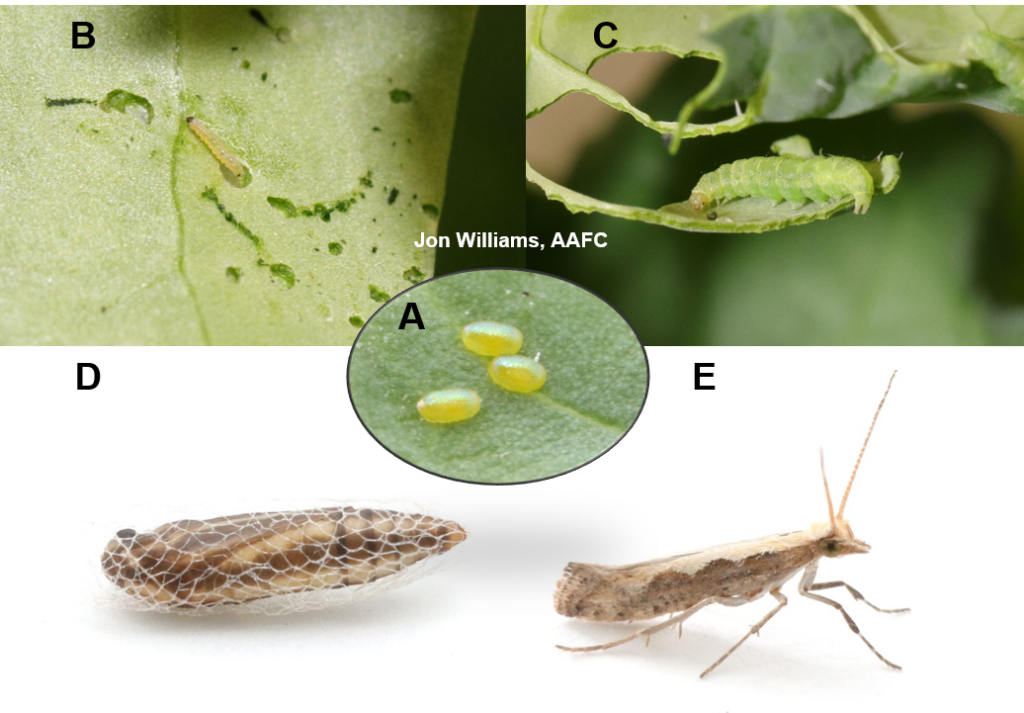

The wheat stem sawfly, Cephus cinctus, is native to western Canada. Its hosts include species of native grasses as well as rye, barley, and winter wheat. It is most economically damaging to spring wheat and durum wheat in western Canada.

Adult wheat stem sawfly do not feed; they live for about 10 days and spend that time mating, dispersing to wheat or durum crops, and laying eggs. Larvae are the damaging stage of the wheat stem sawfly life cycle. Larvae feed on pith inside the wheat stems. Because the larvae feed inside the wheat stems, the damage they cause is not obvious or easy to detect.

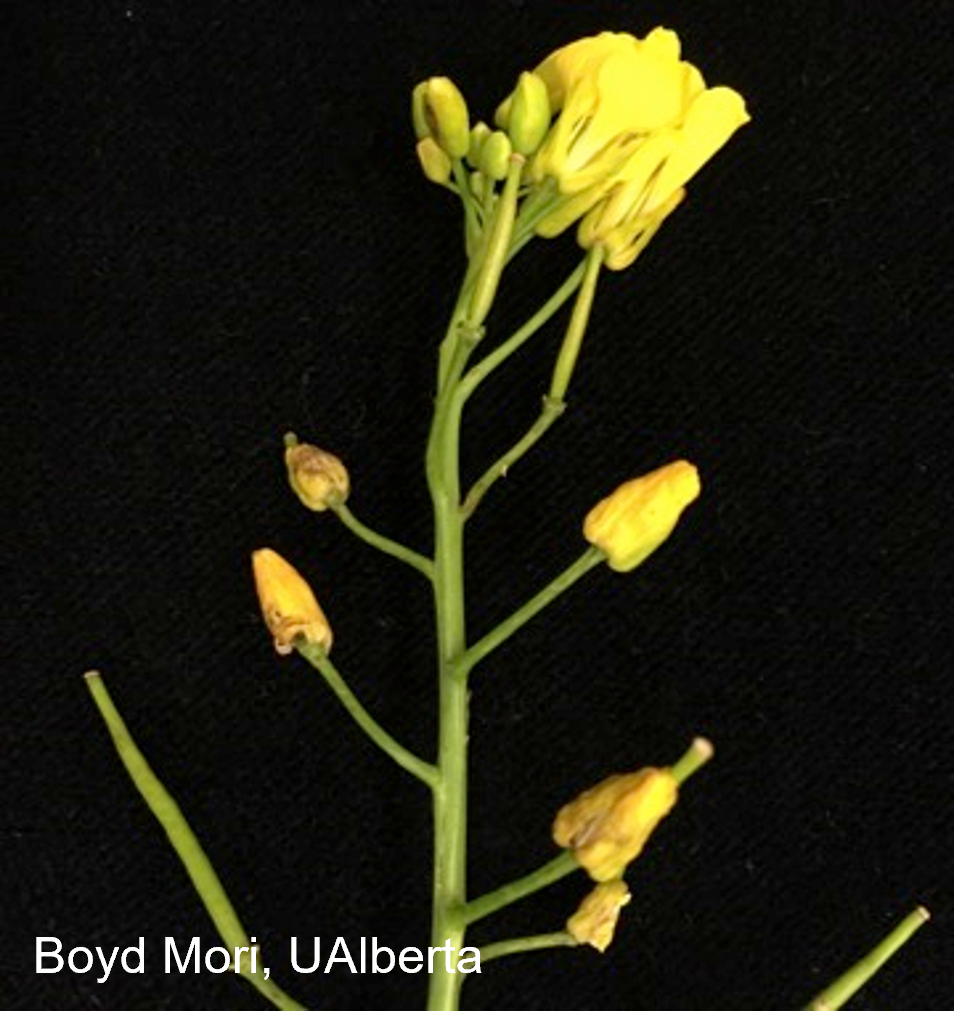

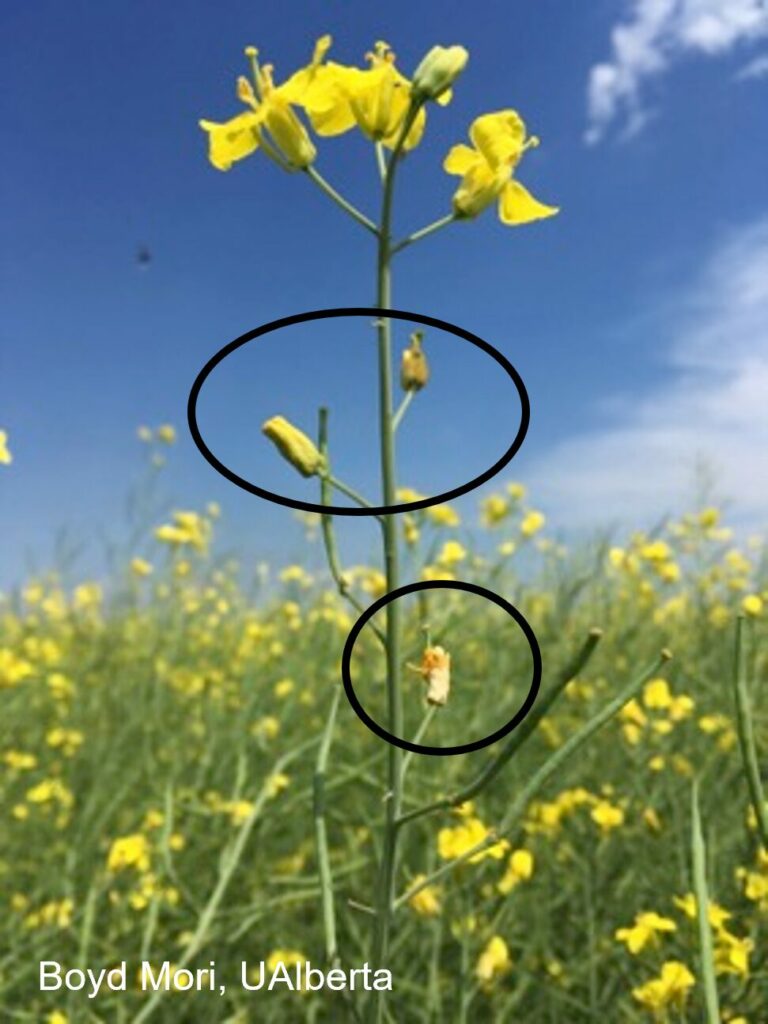

By feeding inside the host plant stems, wheat stem sawfly can reduce the quality and quantity of the grain produced by their host. In the late summer, the larvae also cut the stems of their host plant when they prepare to overwinter. The cut stems are susceptible to lodging.

In the fall, cut stems are used to estimate the density of wheat stem sawfly in wheat and durum fields using the protocol available from the Prairie Pest Monitoring Network. The results of the survey conducted in fall 2023 indicated that wheat stem sawfly densities were quite high in southern Alberta and south western Saskatchewan. Historical maps of the results of the wheat stem sawfly survey are also available from the PPMN Risk Maps page.

Additional information about the wheat stem sawfly is available from the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture and from Alberta Agriculture and Irrigation. For more information, wheat stem sawfly was featured as an Insect of the Week in 2023 and is included in the Field Crop and Forage Pests and their Natural Enemies in Western Canada: Identification and Management field guide. (en français : Guide d’identification des ravageurs des grandes cultures et des cultures fourragères et de leurs ennemis naturels et mesures de lutte applicables à l’Ouest canadien).